Vet Essentials: All about laminitis

Our series Vet Essentials takes a look at some of the common health issues affecting horses. In this article, veterinary surgeon David Rendle takes a look at laminitis.

Laminitis is a debilitating disease of the foot that is associated with severe pain and, all too frequently, death in horses. Conservative estimates indicate that 1-3% of horses may be affected in the UK but some studies estimate the problem to be far worse and in the general pleasure horse population the figure is undoubtedly much higher

The disease is cited as the reason for euthanasia of 1 in 10 horses over 15 years old, and is third only to colic and lameness (both of which actually represent collections of diseases) as a reason for all horses being euthanased. Recent studies have shown that up to 90% of laminitis cases may have an underlying hormonal cause and many of these cases can be managed effectively to prevent painful recurrent episodes of laminitis.

What are the symptoms?

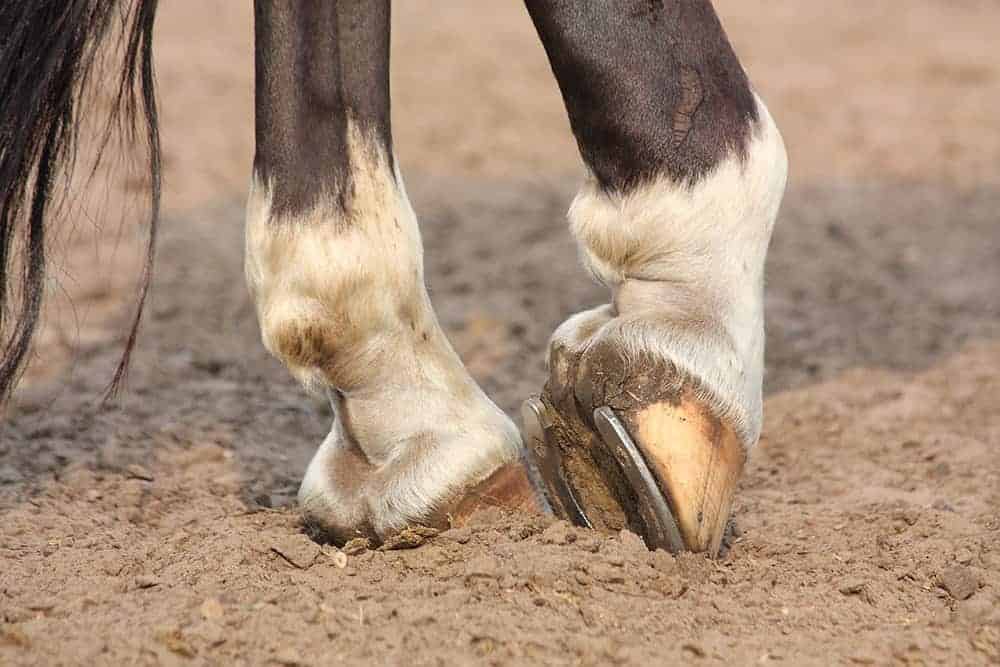

Laminitis refers to inflammation and potentially separation of the connections between the hoof capsule and the pedal bone within the foot. These connections are known as the laminae or lamellae, hence the term laminitis. The horse’s entire body weight is supported by these structures so when they become inflamed the large forces placed upon them can literally pull the tissues apart.

Horses are prey animals and it is not in their instinct to demonstrate pain and suffering so thousands of the animals we love may suffer in silence every year. Horses that “get a bit footy every Spring” or “always have a bit of lammy”, are most likely in considerable pain.

An x-ray of a horse with laminitis showing the pedal bone pushing through the sole of the foot.

Why does it occur?

Laminitis is more common at times when there is a greater sugar content in the grass. Laminitis is also more common in certain breeds, predominantly “easy keepers” or “good doers” that gain weight rapidly. If we turn a Thoroughbred and a Shetland onto lush pasture, it will be the Shetland that gets laminitis. Why? The grass may be the trigger but as only some types of horses are affected it can’t be the underlying cause.

For years researchers have tried to determine why large amounts of sugar (such as fructans which are produced in grass) in the large intestine might lead to laminitis. However, it has since been discovered that the amounts of grass required to cause disturbances in the large intestine and cause laminitis by this mechanism are well in excess of what even the greediest pony can graze.

A breakthrough in our understanding occurred when researchers discovered that in ponies with laminitis, grass sugars could cause large increases in blood insulin levels even when eaten at normal quantities and that high levels of circulating insulin could cause laminitis. Horses that didn’t have a history of laminitis didn’t exhibit this increase in insulin levels.

An overweight horse with equine metabolic syndrome and an obvious cresty neck.

Why are some horses affected?

Insulin is responsible for the storage of sugars as fat in the body. As fat stores develop through the summer, fat releases hormones that reduce the effects of insulin, so-called “insulin resistance”. This insulin resistance then enables the breakdown of energy stores during the winter.

Native breeds have evolved to cope with cycles of weight gain through the summer and then weight loss through the winter and temporary insulin resistance is therefore beneficial. Hot-blooded breeds such as Thoroughbreds and Arabs have been bred selectively over generations for athletic performance and they have developed differences in their metabolism.

Equine Metabolic Syndrome

Domesticated native breeds no longer have to cope with cycles of winter feed deprivation as we provide them with large amounts of supplementary feed. They therefore become more and more resistant to the effects of insulin and if insulin cannot function as it should then the body’s response is to produce more of it, and this hormonal imbalance is thought to lead to the development of laminitis in the majority of cases. This condition in which horses develop fat deposits and then insulin resistance is referred to as equine metabolic syndrome or EMS and has similarities with type II diabetes in humans.

Equine Cushing’s Disease

Older horses may also have high insulin levels from equine Cushing’s disease which is a condition that results from degeneration of the nerves to the pituitary gland in the brain. It is more correctly termed pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction or PPID. It used to be thought that this was a disease of old horses but as our understanding has increased we have appreciated that the disease may start to develop in horses in their early teens or even younger. Degeneration of the nerve supply to the pituitary gland results in uncontrolled production of many different hormones including adrenocorticotropic hormone (or ACTH) and some of these hormones are thought to affect insulin levels.

Two recent studies have shown that collectively, equine metabolic syndrome and equine Cushing’s disease may account for 90% of laminitis cases. This realisation should revolutionise our approach to laminitis as both of these conditions can be managed and laminitis prevented.

The diagnosis of equine metabolic syndrome may be obvious as affected horses are typically overweight. However, some horses with EMS only have regional fat deposits, often a cresty neck, or may appear outwardly normal. In these animals that are not obviously fat, testing may be valuable. A single measurement of blood insulin concentration is helpful, but an assessment of the insulin response to a sugar feed gives a better indication of metabolic changes and is a more sensitive means of assessing the risk of laminitis.

Signs and management

Cushing’s disease is associated with a number of different clinical signs; the best known of which is a long hair coat that fails to shed. However, the outward clinical signs of Cushing’s disease only develop in advanced cases and horses may be at risk of laminitis long before these outward signs develop. A simple blood test of pituitary function can detect these early cases. Cushing’s and EMS can occur together so it is often helpful to test for both conditions.

EMS is managed by diet and increased exercise. Owners of horses with EMS have a stark choice: accept that the horse needs strict dietary management or be prepared for the fact that the horse will continue to suffer from crippling bouts of laminitis. Veterinary advice should always be sought on effective diet plans. Over the years, our perception of what horses should look like has become distorted and equine obesity has become a major welfare concern. We all need to revise our view of what is “normal” weight.

Horses with Cushing’s can be managed very effectively using a drug called pergolide which is proven to compensate for the loss of nerve supply to the pituitary gland. Many herbal and homeopathic alternatives are available but unfortunately there is no credible evidence that they work. For further advice on the treatment of EMS or Cushing’s you should consult your veterinary surgeon.

What should I do?

The majority of laminitis cases are caused by hormonal conditions that can be treated, or at least managed, reducing the risk of laminitis. If you have a horse with laminitis then you should consult your veterinary surgeon and investigate the underlying causes. The costs of a veterinary visit and simple blood tests will be far less than the costs of treating recurrent bots of laminitis and the alleviation of your horse’s horse suffering is priceless.

About the expert

David Rendle BVSc MVM CertEM(IntMed) DipECEIM MRCVS is a Veterinary Surgeon and Specialist in Equine Internal Medicine who works at Liphook Equine Hospital in Hampshire. In addition to being a large referral hospital, Liphook specialises in the laboratory testing of the hormonal causes of laminitis and carries out research in this area.

For more information, visit the Talk About Laminitis website